All, Alone

In 2023, U.S. Surgeon General Dr. Vivek Murthy warned that being socially disconnected is as deadly as 15 cigarettes a day. But unlike giving up smoking, you can’t fight isolation by cutting something out — you need to incorporate something new.

In 2021 I was new to D.C., fresh out of college, living alone, and struggling. Everything from the dishes in my sink to my daily step count was a reflection of a deteriorated mental state. In all the city I had one friend from college, a handful of acquaintances who stayed acquaintances, and a few work friends who stayed work friends.

I thought it was a chicken and egg situation, being depressed and isolated, that ultimately fell on my shoulders. I felt broken, but I didn’t realize what did the breaking. I’ve since discovered what can do the healing.

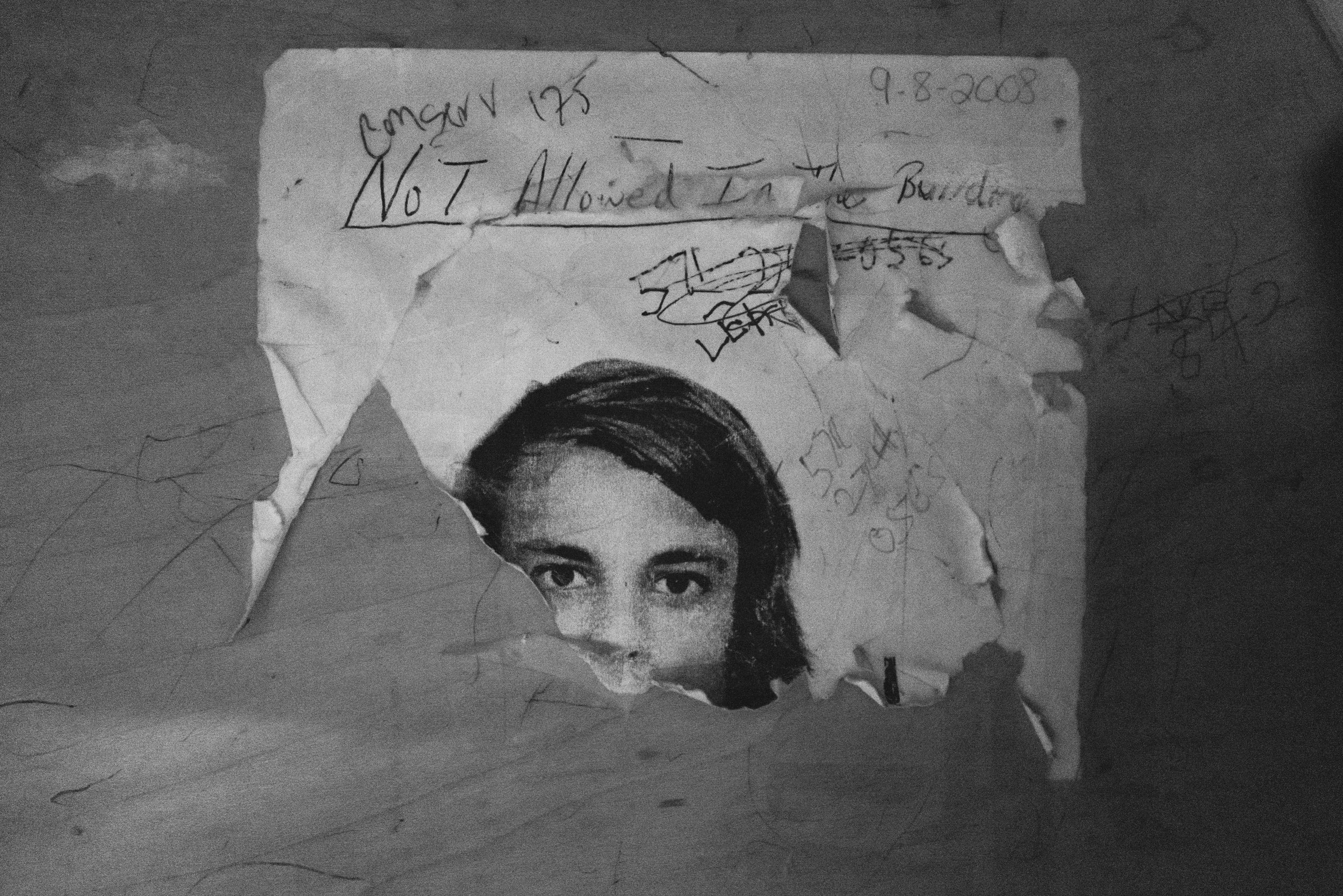

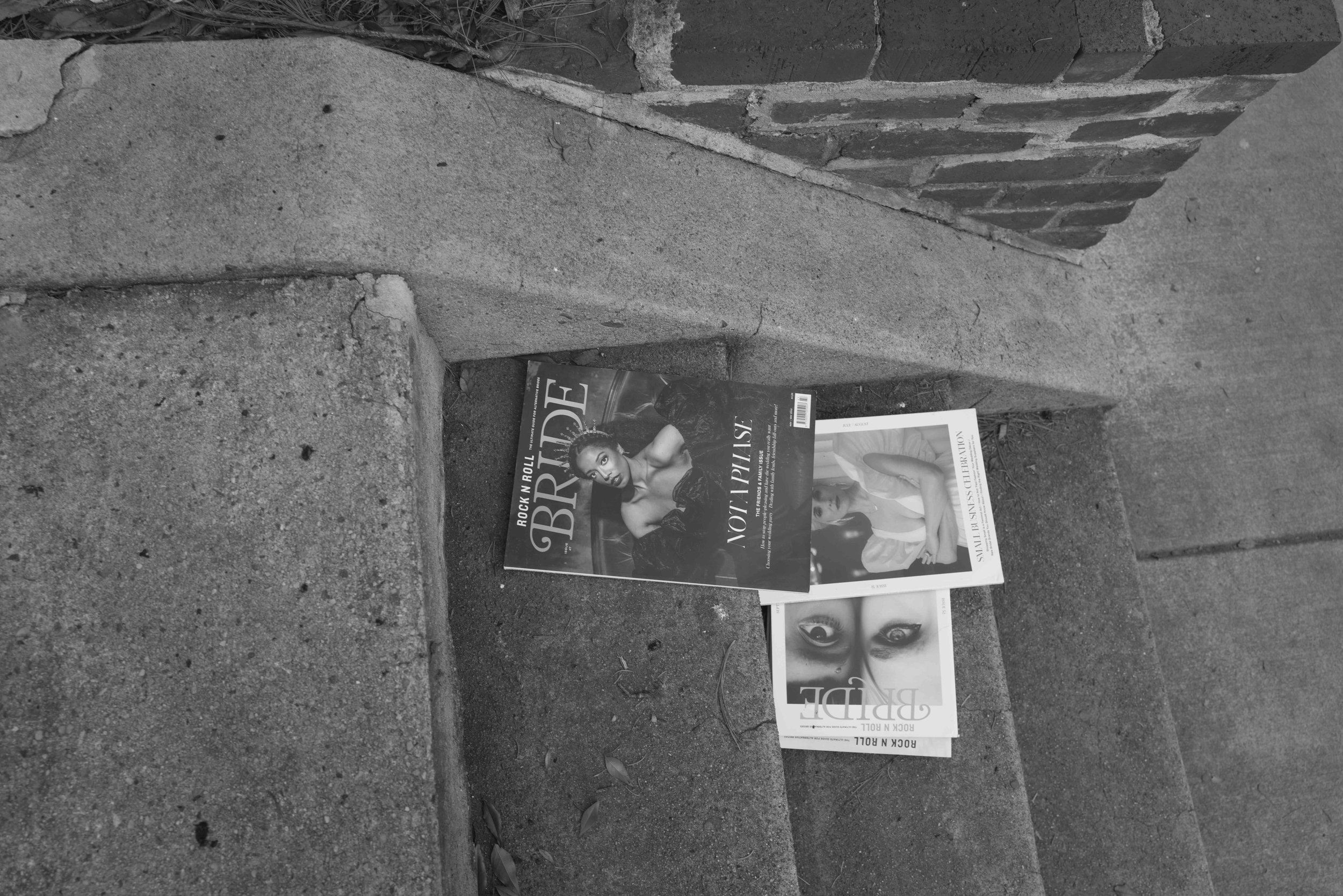

All, Alone is a two-sided coin, or perhaps both the chicken and the egg. The photographs allude to the claustrophobic world of isolation. The video Showing Up holds the vivacity of Northeast Track Club, a local community that’s part of thousands of people’s lives – a solution, a hello to new futures.

Showing Up will find a home online after being shared with audiences at film festivals.

Meeting people as an adult, in the city with the most single-occupancy households in the country, in the wake of a pandemic, is a challenge. Northeast Track Club is leading the way in building a supportive and inclusive space in which each individual can show up every Tuesday, just as they are, and walk out as a part of a community. Showing Up is that story.

All, Alone

Social isolation is a risk to your health, and Americans are alone more than ever. What are we to do?

By Noah Weeks

“I have no need to get support from anyone, right?” he said. “I can order my food to the door, I work from home, I work out here, I can do laundry in here.”

Zach Ernst can do it all from home. Or so it may seem.

By himself in the north wing of an Arlington apartment complex, Ernst works remotely as a software engineer; a six-figure job he landed after a career change and six months of “coding bootcamp.” Work is hardly strenuous, physically, so Ernst goes out of his way to exercise. Granted, it’s not far. Just a lazy arms length behind his tri-monitored desk a yellow-and-black squat rack stands sentinel, itself a forearm away from his bed. Combined with the pizzeria and ice cream parlor downstairs, just a short hallway’s walk away from the building’s lobby, Ernst doesn’t need anything else.

Unless he wants to avoid the risk of premature death due to social isolation, which is comparable to the risks associated with smoking about 15 cigarettes per day.

That’s according to “Our Epidemic of Isolation and Loneliness,” an advisory published by Surgeon General Vivek Murthy on May 3, 2023.

Surgeon general advisories “are reserved for significant public health challenges that require the nation’s immediate awareness and action.” Historically, people have listened: In 1964, one was published on the danger of smoking cigarettes; One year later, Congress mandated all cigarette packaging include health warnings; Six years later, advertising tobacco on television and radio was banned.

The advisory is a medical wake-up call. A collective “give it to me straight” conversation with the nation’s top doc.

And it turns out, us humans are scientifically-proven “people people,” very much for the better, or very much for the worse. Everything from cardiovascular health to voter turnout to carjacking rates is predicated on our existence as social beings. And unfortunately, we aren’t doing a good job at it.

Thanks to the conveniences of modern American life, we are now self-sufficient to a fault for the first time in history.

“We have to go out of our way to exercise now, and I think that's a great analogy to having to go out of our way to socialize now,” Ernst postulated. “It's the same thing. The socializing, the exercising—as things have stopped being a side effect of just surviving, now you have to go out of your way to kind of recreate those bonds.”

Friendship should be natural. But it isn’t always.

In the beginning was the first word, the first step, and the first friend—and we make sure of it, measure it, and celebrate it.

From the CDC’s list of childhood milestones, with milestones such as “plays next to other children and sometimes with them,” to mandatory school attendance, as a society the United States recognizes the importance of social connection for children.

The socially-nurturing environment of school, for Ernst, led to lifelong friendships. In middle and high school, Ernst made friends easily while playing in “basically every band possible, except for marching band.” It felt as natural as hearing “I Want It That Way” by the Backstreet Boys and knowing the guitar’s playing Em, G/D, C, Am, and D chords.

“I’m not sure if it’s something you’re born with, but I’ve always had it.” That attitude is perhaps why he’s so humble about having perfect pitch; it isn’t even on his Hinge dating profile. But he admitted, over text, “yeaaaaa, time to lean into it a bunch.” It helped him make friends, so why wouldn’t it help find a partner as well?

Outside the classroom, he was part of a band, Diner Road, with Chris on guitar, Mikey on drums, and Earnst on bass. They did covers, and he recalls, “I think we played at the local library.”

After graduating from high school, he stuck around northern New Jersey, continuing to live with his mom and stepdad while studying at the county college. Much of his friend group stayed in the area too, and with two of them, Jake and Sal, Earnst formed a new band, Pyramid Mountain. Jake was the “genius songwriter” behind the band’s original songs; Sal was a “virtuoso drummer” who now plays professionally in multiple bands.

“I had my friends from middle school and high school that I still, to this day, am very good friends with, so I didn’t really feel the need at that time to kind of go out and explore,” Ernst said. There was no impetus to join his college’s extracurricular activities, so he didn’t.

The status quo remained largely unchanged. And just when Ernst, then 24, began to feel “stuck,” he heard someone banging on the front door.

On a Saturday evening in late 2019, following a “frantic” woman into her boyfriend’s house next door, Ernst, his mother, and stepfather found their neighbor hanging from a staircase railing.

He remembers his mother cutting the man down and beginning CPR—she “had her own traumas from that”—and his stepdad remaining stoic—”he was okay.”

“But I kind of lost it at that point,” Ernst recalled.

Face to face with rock bottom, Ernst took stock of himself. “I was like, all right, I’m not working where I want to work. I’m not living where I want to live. I’m not doing what I want to do. My life is not going the way I want it to.”

That experience was the first catalyst for reinvention. Shortly after, he lost more than 70 pounds and became vegan, and he started a running habit that would lead to run a full marathon in 2022.

Shortly after the first came the second catalyst: his ex-girlfriend, Christina. She was a remote software developer, living in New York and later in D.C., and the two of them built what felt like a healthy long distance relationship—meeting up for a week in Philadelphia here, a vacation in Florida there.

However, things with Christina ended poorly. “This girl was not who she presented herself as, and I learned that the hard way later on…To this day, I don't know what the true story is with everything.” The gist is she was in another relationship, the whole time.

But early on, Ernst felt inspired: “She lived the kind of life I wanted.” So he trained as a software engineer and landed a job that ticked all his boxes: remote, challenging, and well-paid. He could move anywhere and survive untethered.

After the breakup, despite Christina living in proximity, Ernst decided he still wanted to move to D.C.

Ernst was joined a growing legion of young professionals living alone and working remotely.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau American Community Survey, the number of Americans living alone increased by 2.4 million since 2019. In Washington, D.C., single-person households account for 48.6% of all households; In Alexandria, VA, that number is 43.6%. Compared to all the major cities in the United States, they rank first and eighth respectively, making the DMV one of the loneliest regions of the country.

Meanwhile, the COVID-19 pandemic has ushered in a paradigm shift in how we work. At its peak in October 2020, remote work accounted for 55% of jobs in the U.S. Today, that number’s holding steady at 35%, a fivefold increase compared to pre-pandemic levels.

So how, exactly, does a remote worker living alone make friends in the loneliest place in the country?

The bottom line is: You need to go out of your way, walk into a space alone, and come out of it less alone.

For Ernst, making new friends meant flexing muscles long dormant. However, “being alone on a Saturday night is a very big motivator to go out and find some group to get to know.” The easiest place to start, for him, was online.

In the nearly three decades since Match.com launched in 1995, the stigma of starting romantic relationships online has steadily declined. Today, one-in-five adults in the U.S. under 30 in a romantic relationship met their partner on a dating site or app, and four-in-ten adults say those resources make the search for a long term partner easier.

The same cultural acceptance isn’t as present for meeting friends online. When it comes to dating, there’s the expectation that it takes work to find a good match—lots of first dates, a significant investment of time and energy, and a lot of hit and miss—which makes online dating an efficient tool. Making new friends can take just as much effort, and although less common, technology can be used to “date around” for friendships as well.

Ernst started by visiting r/washingtondc on reddit, a forum where posters can share events and plan get togethers. “It’s not anything excessively different from any other tool you use to meet someone, right?”

At one of the forum’s weekly happy hours, Ernst met his first and best friend in D.C., Seth. It turned out Seth plays guitar, and they instantly connected over a love of music. That friendship was a foot in the door to Seth’s larger social network in the city, and soon “whenever [Seth] and his friends have a house party, I’m always kind of invited alongside.”

After finding success connecting over music, Ernst set out to find people who share another of his passions: running. Thanks to its burgeoning popularity on Instagram, where it “sports” about ten thousand followers, Ernst discovered Northeast Track Club, or NETC.

Sitting in the stands of Cardozo High School’s track and football stadium, Zach listened as one of the founders of the club, Matt “Track Dad” Kesting, called for all the new folks to stand up and come to the front to pick up a bright yellow wristband.

Matt announced to the crowd of about 300 runners: “Please remember your first time here, and try to make whoever has a green wristband on, make their first time here better than your’s was, make them feel a part of this, if you would.”

From the start, it was clear to Ernst that here was a community where socialization was taken seriously—a structured environment where meeting people and growing together are the bottom lines. On the track, there’s an eagerness to be friendly and supportive not always present in much of modern adult life, such as at work.

And the club’s friendly ethos extends beyond the track, and in December of this year Ernst attended the NETC Winter Gala masquerade party—donning a black-and-gold paisley vest and a steampunk mask reminiscent of Star-Lord’s in Guardians of the Galaxy.

“It’s a good conversation starter,” he quipped.

Within four years, starting when he was 25 after the loss of his neighbor, Ernst had taken control of his life and transformed nearly every aspect of it.

The endeavor took, and takes, great effort, determination, and initiative. Ernst’s formula worked for his career, his health, and his friendships—and, he hopes, it will work for dating soon as well.

When asked where he gets the motivation, it was clear Ernst had posed to himself the same question before.

“Often, people are better at doing things for other people than themselves,” reflected Ernst. However, “in your life, the person you will always be with the most is yourself. And for that reason, you need to take care of yourself. You have to be your own best friend. You have to be your own best partner. Because no matter who comes and goes in your life, friends, relationships, you will always be there for you.”

It’s sort of like cleaning your house before hosting a dinner party. Although you’re the one who spends the most time in your home, you may only be motivated to clean it so your guests feel comfortable and leave with a good impression; your house is clean after they leave, and you reap the long term, personal benefits of an external, social motivation. And then having a clean space may make it easier to invite people over in the future. It’s a mutually beneficial feedback loop.

In this mindset, the key to being more social—making friends, meeting a partner, finding a community—is, ironically, focusing on oneself.

“If people start to treat themselves better, you might see, you know, less loneliness,” Ernst said. “People might start to connect to each other a little bit better because they're taking care of themselves better.”